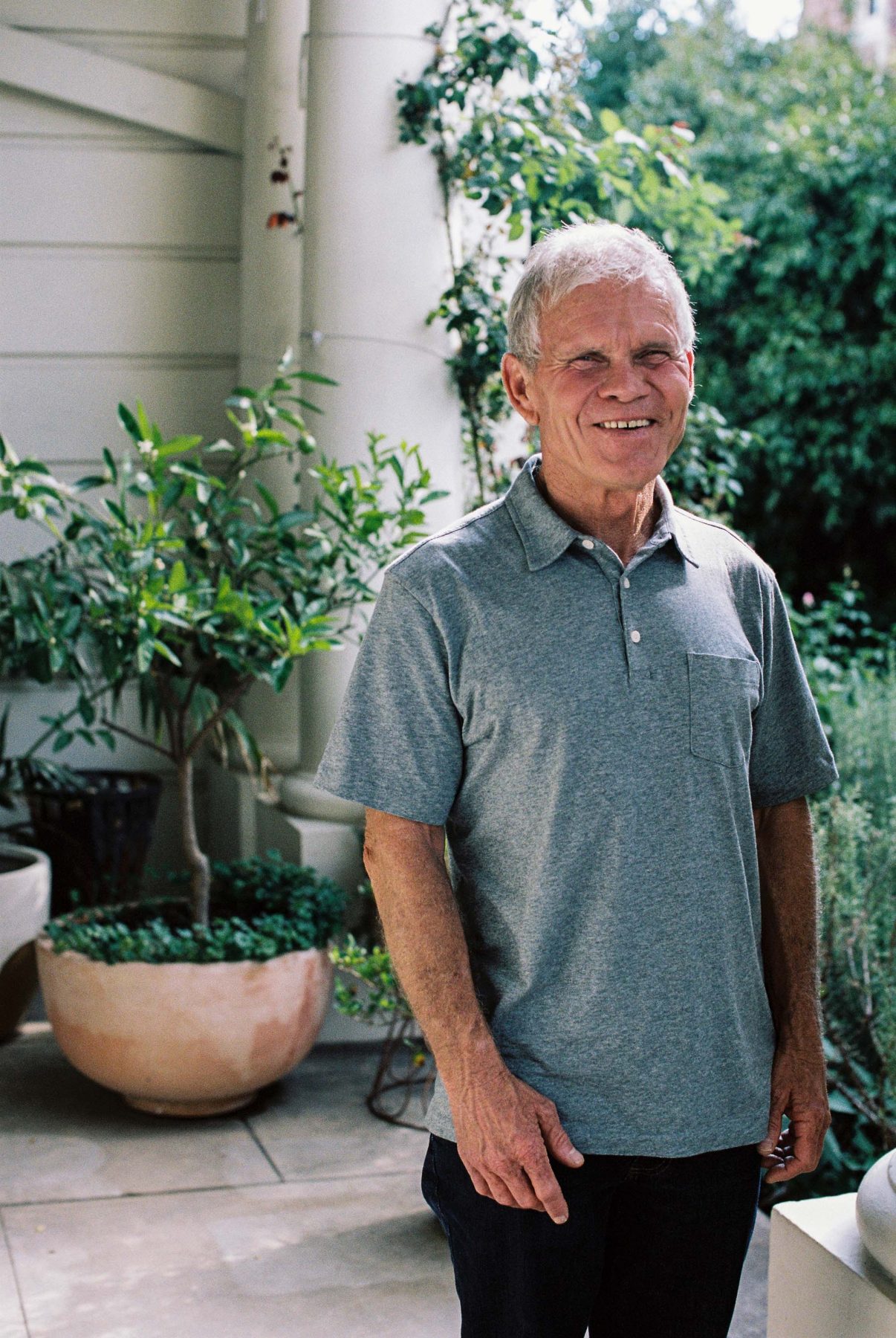

Profile

Rick Ridgeway

Rick is the Vice President of Environmental Affairs at iconic outdoorwear label, Patagonia.

Sigrid: What do you love most about working with Patagonia?

Rick: What I love most is the sense of family and inclusion that is so foundational to the company’s culture. I’ve been involved with the company since it started in the early 70s. Yvon and I have been friends and mountaineering partners for over forty years—probably over forty five if I thought about it long enough (laughs)—and we would often surf together and go on climbs. Back then, before Patagonia was Patagonia, it was a small company making equipment for mountain climbers.

Right from the beginning I did freelance work for the company, mostly in marketing as a photographer and a writer. Then in the early 80s when I married my wife, Jennifer, she moved to Ventura to join me. She had been in the clothing business herself prior—she was one of the very first employees at Calvin Klein and worked very closely with Calvin to develop his brand. In the beginning it was just the two of them, and their business manager, making calls on all their key accounts to start the company. She would dress up in the high fashion line and walk into meetings with Calvin; she would present herself and he would talk about the clothes she had on and that’s how they started..

She moved to Ventura and took a job at Patagonia. When she interviewed with Patagonia’s CEO, Kris Tompkins, Kris said ‘Ok we need you in marketing’, and my wife replied ‘I don’t know anything about marketing.’ Funnily enough Kris assured her ‘Neither does anybody else here’ (laughs). We then had our first daughter shortly after that, and Jennifer would bring our daughter to work and put her in a bassinet under the desk. Our daughter was a wailer so she was constantly interrupting the workplace, and Jennifer didn’t have a private place to breastfeed our daughter, so Melinda—Yvon’s wife who co-owns the company with Yvon—got a trailer and parked it out the front of the office building and hired a babysitter. Pretty soon more babies arrived and the trailer filled up, and then Melinda moved it into another room that she renovated to be the daycare centre for the company.

Today, Patagonia is arguably the leading company in the United States for on-site daycare. My daughter now has a two and a half year old herself that I bring into daycare every day; who rides in with me. I sometimes have lunch with her and we play out in the field, in the playground, which is on our campus. When visitors have come to Patagonia, many have paused while on the tour and said, ‘Gosh this feels just like a family.’ And I reply, ‘Well, stop and be quiet for a minute; what do you hear?’ They comment on the sounds of the kids playing in the playground (laughs). It feels like a family because it is a family. Here we are, with the third generation of our family in Patagonia’s daycare.

And so.. That’s a very long answer to your question (laughs) as to what I find most valuable about the company—its sense of family.

Sigrid: A lovely answer.. It’s beautiful having the opportunity to work for a company that is shaped by such strong values. Other companies could surely learn from Patagonia in that sense.

Rick: At this conference yesterday, my mission was to try and identify the parts of our business that have underpinned our success. Elements that I think can serve as examples for other companies; that can benefit them—whether they are a privately held mission driven company like we are, or a large publicly held company. I think one of, or even the most important business values that comes from sustainability commitments, is the ability that companies have to attract the best and brightest young people coming out of our schools today. This is so clear to those of us who work for companies that have those values, yet surprisingly unclear and not necessarily obvious to so many other large, traditional companies that I encounter. They don’t seem to understand quite yet that they are at enormous business risk by following the traditional business models—the models that are focused solely on delivering returns to shareholders, instead of sharing values with stakeholders.

When I go to business schools and I look into the eyes of the students who I know are interested mostly, and sometimes exclusively, in companies who have these values.. I end my talks to them by saying, ‘This is over to you. You guys are the ones that have to find solutions to these problems that my generation created. And you have the power to do it. One of the biggest levers in your hand is your ability to say no; the ability to refuse to work for anybody, or any company, that doesn’t have these kinds of values.. The type of company that doesn’t operate with commitments to wider society and focuses only on shareholders and profit.’

Rick Ridgeway

“All of our values stem from our time in the wild; they can all be traced back to what we learned in these places.”

Sigrid: Absolutely. How have your personal values shaped your work or influenced the culture at Patagonia?

Rick: Yvon and I, and the majority of people at Patagonia in the early years—and even the majority of the people working there now—are all dedicated outdoor people. Not surprisingly.. We started off by making gear for ourselves, because we couldn’t get it elsewhere. That’s how Yvon got started; first with the mountain climbing equipment and then later with the clothes. He was inspired by the need to make the gear he required as an ‘outdoor athlete’, which is what they call people like us today (laughs).

Being climbers and mountaineers, and surfers and skiers in the backcountry—out in the wild parts of the world—we firsthand began to witness the degradation of the places we loved. Sometimes people ask me what my favourite climb is in the world, and I can say that it was an ice climb on Mount Kenya in East Africa. A mountain that is above 17,000 feet in elevation and right on the equator; the equator goes right through the flank of the mountain. Back in the ‘80s, there was a ribbon of ice on one side of the mountain that was a spectacular climb.

There were two routes—Yvon did the first descent of one of them, and I climbed another ribbon of ice right next to the one he did a few years later. It was magical to have an extraordinarily beautiful climb on ice right on the equator, where approaching the mountain you could see elephants through the jungles with glaciers behind them. I say ‘was’ because it has gone now; it’s forever gone. It has melted and never to return as long as we can see out into the future.

We’ve also witnessed firsthand, in addition to climate change, the fragmentation by human beings’ development of so many of the forests, mountain ranges, former grasslands; the places that were so close to us. When Yvon first went to Patagonia, the place, in Southern Chile and Argentina in the late 1960s, he did an ascent of an emblematic peak called Fitzroy. This is actually the skyline of our label—it’s there because that climb was so important to Yvon; it so informed his values and who he was. It was arguably the most formative experience of his life, because it was such a wild place in the world. Five years later, when he started the clothing line, he wanted a name that embodied the wildness that the clothes represented. He wanted to create gear for people going out into the unknown parts of the planet. So that’s where the name comes from, Patagonia..

Twenty years later I actually returned there with Yvon, to the exact same place, and instead of wilderness we passed through surveyor stakes all laid out in grids for the development of what is now a city. There was nothing there when we first went to that place, so this is yet another example of how in our own lifetime we have witnessed change. As people who’ve loved and continue to love wilderness and the wild lives that these types of places support, we can’t witness these changes and not respond. And that’s what has informed our environmental commitments at Patagonia.. It’s our time out in the oceans and the mountains, and how that time has shaped who we are as people, that has directly informed the business and its culture. Not just our environmental commitments, but how we do everything.

The commitment to family culture at Patagonia, that has come out of the mountains too.. As outdoor people, we created a business to support our habits (laughs). That is why we started. We wanted the gear for the places we loved; we wanted a company to capture all the things we hold important in our lives. This includes being able to leave the business when we want to go surfing, or when we want to head out to the mountains. We built the business to be flexible; we built it to be inclusive; we built it to be a family. We didn’t want a business that was separate from the rest of our lives; we wanted to integrate the whole thing so that there was no unnecessary separation between work and life.

All of our values stem from our time in the wild; they can all be traced back to what we learned in these places..

Sigrid: Patagonia is unique in many ways, most notably in its approach to transparency and willingness to admit fault publicly when issues are found in its supply chain. Do you think companies need to focus less on being perfect and more on their journey towards doing ‘better’?

Rick: Yeah.. We have a way of running our business that can and should be an example for other businesses. As you’ve just said, our definition of transparency at Patagonia is the good, the bad and the ugly. You may know that our mission statement is to build the best product but to do it with no unnecessary harm. The words ‘No unnecessary harm’ have been very carefully chosen; we don’t say ‘the least harm’, we say ‘no unnecessary harm’ because it’s a double negative—so it’s grammatically incorrect—and if you take out the two negatives, the double negatives, you’re left with ‘causing harm’.

Our definition of manufacturing is that it inevitably causes harm; you can’t make stuff without creating damage to the environment; without taking resources from it. If you really analyse it, no matter how hard you try, it’s kind of unsustainable.. So, if you know that you’re doing harm, the goal becomes to do no unnecessary harm and you recognise that you’re going to be doing some necessary harm—no matter how hard you try to avoid it. Think about that for a while and you realise that what you’re doing is recognising the good and the bad. And if you know that you’re doing bad, as well as good, it’s immoral not to be transparent about that; not to share that..

Rick Ridgeway

"It’s our time out in the oceans and the mountains, and how that time has shaped who we are as people, that has directly informed the business and its culture. Not just our environmental commitments, but how we do everything."

Sigrid: Yes, I think it’s so important to have companies like Patagonia acknowledging issues when they arise in their supply chain, as as way of influencing other businesses to embrace transparency and not shy away from the ‘bad’.

Rick: We can explain to other companies that when you do admit fault publicly, it’s not the end of the world; the world does not come down on you. Rather, the world recognises your honesty and rewards you for it. But it does take a little bit of courage, and it’s definitely not something that most companies are used to doing. There was an incident at Patagonia about two or three years ago—some people in our production department came into a senior executive meeting, and they told us they had discovered some issues in our second and third tiers of the supply chain. In Taiwan mills and dye houses, the workers had been imported from the Philippines by labour agents who had charged them for their transport and living expenses during their travel to Taiwan. The agents, with the people owning the mill, had then confiscated the workers’ passports and would not give them back until they had earned back the fees for their own transport to take on these jobs. In some cases, this was going to take workers two or three or four years..

Essentially, the Patagonia production department sat at the table during that meeting and said, ‘We’ve concluded that Patagonia has slaves in its supply chain.’ Because that’s what it was, indentured servitude.. You can find some fancy word for it, but at the end of the day it was slavery. I can guarantee you that just about all companies you can imagine—regular public, traditional companies—would handle this situation the same way. If someone was at a table and said that they’d just discovered the company was supporting slavery, they would close the door, call in the lawyers and immediately start to talk about how to keep it hushed up.

At Patagonia, the first thing that happened was everyone looked around the table and said ‘Oh my god, we need to fix this.’ And then somebody acknowledged, ‘Well we can’t fix this on our own, we need to work with the government. This is a policy issue, we need to work with NGOs too, we need their help. We should reach out to other companies and embrace a multi-stakeholder approach. We’re going to need everybody on deck to support this, and we need to go public with this right away. We need to tell people we have a problem here, and we need help to figure out how to fix this.’

Sigrid: Well from a business perspective, and a risk management perspective, surely it’s riskier to attempt to keep these types of issues a secret..

Rick: Of course it is, but how many people recognise that? And certainly as a first reaction to a discovery like this, it’s not common for someone to think ‘We need to go public’ (laughs). But that’s part of the company’s culture, and it’s our definition of transparency. That was a particularly proud moment for me.

CONTINUE READING PART TWO OF INTERVIEW

Photography: Claire Summers

Production & Interview: Sigrid McCarthy

Thanks to The Bravery

Learn more about Patagonia